FEDERAL JUDGE JAMES HERBERT WILKERSON

Zenith Radio Corporation (WJAZ)

From a biography of the John Wilkerson Family by Olen Smith in One Hundred Years of Helena All Because of a Railroad 1878-1978

“John Wilkerson’s [this is John Wilkerson Jr.] son James Herbert, was born in Savannah, Missouri on December 11, 1869, and was graduated at De Paw University in 1889. He gave early promise as an orator, winning in the interstate Oratorical Contest of his senior year. He taught school for a number of years and was admitted to the bar in Chicago in 1893. Mr. Wilkerson was a senior member of the law firm of Wilkerson, Cassels, Potter and Gilbert, with offices in the Rookery Building. He was appointed to United States District Judge for the northern district of Illinois to succeed Kenesaw Mountain Landis, who resigned from the bench to become Commissioner of Baseball. The name of Mr. Wilkerson was sent to the Senate by President Harding and speedy confirmation was predicted. He helped crush the most notorious gang in the United States and was cited for his reward.

President Hoover announced his advancement to the Circuit Court of Appeals, seventh district, saying it was part of the recognition for brea king up the activities of the powerful Capone Gang, “Scarface Al” Capone. Judge Wilkerson sentenced him to eleven years, fined him $50,000, and refused to grant bail.”

He was a federal judge in the Northern District of Illinois 1911 to 1914. He sentenced Al Capone, and earlier in his career as U.S. District Attorney he secured the famous $29,240,000 fine assessed on the Standard Oil Company by the then Federal Judge Kenesau M. Landis.

“On April 23, 1930, the Chicago Crime Commission issued its first Public Enemies List; there were 28 names on it, and Al Capone’s was the first. Capone headed an enormous crime organization that netted huge profits from the illegal liquor trade and he became a legendary symbol of the violent gangsterism of the Prohibition era.

For years Capone remained immune to prosecution for his criminal activities. In June 1930, after an exhaustive investigation by the federal government, Capone was indicted for income tax evasion. One of the most notorious criminals of the 20th century–the man held most responsible for the bloody lawlessness of Prohibition-era Chicago–was imprisoned for tax evasion.

The trial was highly publicized. Hollywood celebrity Edward G. Robinson, who had portrayed a Capone-like character in the movie “Little Caesar,” attended 1 day to observe the gangster role model, Capone. The names, addresses, and occupations of the 12 jurors who decided the case and signed this verdict were printed in Chicago newspapers. To reduce the chances of jury tampering, the judge tried to keep the trial as short as possible and confined the jury at night.

During the trial, the prosecution documented Capone’s lavish spending, evidence of a colossal income. The government also submitted proof that Capone was aware of his obligation to pay federal income tax but failed to do so. After nearly 9 hours of deliberation, the jurors found Capone guilty of three felonies and two misdemeanors, relating to his failure to pay and/or file his income taxes between 1925 and 1929. Judge Wilkerson sentenced Al Capone to serve 11 years in prison and to pay $80,000 in fines and court costs.” Source: National Archives

From the Al Capone website: In 1931, Capone was indicted for income tax evasion for the years 1925-29. He was also charged with the misdemeanor of failing to file tax returns for the years 1928 and 1929. The government charged that Capone owed $215,080.48 in taxes from his gambling profits. A third indictment was added, charging Capone with conspiracy to violate Prohibition laws from 1922-31. Capone pleaded guilty to all three charges in the belief that he would be able to plea bargain. However, the judge who presided over the case, Judge James H. Wilkerson, would not make any deals. Capone changed his pleas to not guilty. Unable to bargain, he tried to bribe the jury but Wilkerson changed the jury panel at the last minute.

The jury that convicted Capone consisted almost entirely of rural, white men. Among them, a retired hardware dealer, a country storekeeper and a farmer. Judge Wilkerson substituted this jury for the original jury to prevent tampering. (CHS DN 97016)

The jury found Capone not guilty on eighteen of the twenty-three counts. Judge Wilkerson sentenced him to a total of ten years in federal prison and one year in the county jail. In addition, Capone had to serve an earlier six-month contempt of court sentence for failing to appear in court. The fines were a cumulative $50,000 and Capone had to pay the prosecution costs of $7,692.29.

On September 1 a federal judge James H. Wilkerson issued a sweeping injunction against striking, assembling, picketing, and a variety of other union activities, known as the “Daugherty Injunction.”

Although the strikers were without pay, the railroads were without skilled mechanics for their maintenance-intensive steam locomotives. From August through September 1922, 71 percent of the nation’s locomotives failed their monthly inspection. Rank and file members of the operating brotherhoods were restless and sporadic sympathy strikes were breaking out, totally shutting down some railroads. A national court injunction broke the strike’s backbone. President Warren Harding made a faint hearted effort to negotiate and involved Secretary of Commerce Hebert Hoover and Labor Secretary John Davis in mediation, which both took seriously. By the end of August Attorney General Harry Daughtery, who was militantly anti-union, convinced Harding national action was needed. On September 1 newly appointed federal judge James H. Wilkerson of the U.S. District Court in Illinois handed down one of the “most sweeping federal injunctions in U.S. history (Davis, 131).” The injunction outlawed picketing, “loitering and congregating” near railroad facilities, communication about the strike between workers or from their union and the use of union funds to support strike activities (ibid., 130-131).

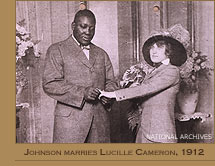

The U.S. Department of Justice began investigating Jack Johnson for possible violations of the Mann Act almost from the moment the law went into effect in 1910, but prosecutors did not find an incident from which to build a case for over two years. On October 11, 1912, Mrs. F. Cameron-Falconet came to Chicago, accusing Johnson of kidnapping her daughter, Lucille Cameron. In less than one week, Johnson was arrested by Chicago police on state kidnapping charges, and U.S. District Attorney James H. Wilkerson began building a federal Mann Act case, despite cautions from Attorney General George W. Wickersham. Lucille Cameron, though not cooperating with investigators, was brought before a Federal grand jury. The Mann Act case fell apart when it became clear that Cameron had been a prostitute before she left Milwaukee and had been in Chicago for more than three months before she’d first met Johnson. On December 4, Johnson and Cameron were married.

Zenith Radio Corporation (WJAZ)

The first radio “piracy” case fizzled last week in Chicago. The Zenith Radio Corporation (WJAZ) of Chicago, hampered by Secretary of Commerce Hoover’s administrative regulation that it have only two hours’ broadcasting time each week, decided to make a test case of his authority. They deliberately prolonged their broadcasting time on their licensed wave length (322.4 meters; also that of General Electric’s Denver Station KOA), and deliberately used the wave length of Canadian stations.

If WJAZ could snatch without restraint at any wave length it pleased, other stations could do the same. Aerial chaos would result. So radio listeners with $500,000,000 to $600,000,000 invested in receiving sets waited for a court decision. More anxiously waited the radio manufacturers and broadcasters, who realized keenly that broadcasting must be constant over wave lengths and time.

Thus the Zenith people were arraigned for criminally violating the Federal statute of 1912 on the subject, and the only one. This statute regulates the licensing of manufacturers, producers and experimenters in radio, gives little discretionary powers to the Secretary of Commerce over regulating broadcasting, provides few regulations in itself. This statutory lack Secretary Hoover has filled by his administrative orders, among others the assignment of wave lengths and of broadcasting hours.

Federal Judge J. H. Wilkerson decided that, as the Zenith people had been licensed regularly, they had committed no crime. Neither was their violation of the administrative regulations a crime. He carefully avoided a construction of the Congressional law (the statute of 1912) dealing with the subject, which might render that law unconstitutional. Thus the conditions remain undecided, unchanged, although sentiment seemed coalescing to make more detailed the statutes or to make more effective Secretary Hoover’s regulations

The Commerce Department challenged Zenith’s move, and the case ended up in Federal Court in Chicago. In his April 16, 1926 decision, Judge James H. Wilkerson sided with WJAZ on its right to choose its own frequency. However, Wilkerson’s ruling mainly addressed the legality of WJAZ’s frequency shift, and did not delineate exactly what Hoover could and could not do. The Commerce Department debated whether it should appeal the WJAZ ruling. In the meantime, everyone looked to Congress to pass a new law to stabilize the situation. Congress promptly dropped the ball. Although both branches passed new laws, they were significantly different, and Congress adjourned in early July before the differences could be worked out in committee. Congress would return in session on December 8th, after the elections. Until then Hoover was on his own.

Dallas Morning News, 10.5.1931, Washington March 12 – Judge Hames H. Wilkerson who sent Al Capone to jail withou bail was given a pat on the back Saturday by President Hoover…. The President is willing that it be know thathe has proposed Judge Wilkerson be advanced in recognition of his sevices in fighting organized crime and gansters. He feels that such splendid services in behalf of the public and against gangland activities should be recognized and he made it clear such services would be recognized. Wilkerson’s nomination for advancement to the Circuit Court is now before the senate. The Judge is facing labor opposition because of injunctions he granted in labor disputes.

JUDGE WILKERSON, S.H.S. GRADUATE DIES (1948) – James H. Wilkerson, 79 year-old former senior judge of the United States district court in Chicago, a graduate of Savannah high school at the age of 14, died September 30 in Glencoe, Ill. HIs father John W. Wilkerson, was superintendent of schools at Savannah for a number of years. Judge Wilkerson’s most famous case was when he sentenced Al Capone, Chicago underworld leader, to federal prision for 11 years and fined him $5,000 for income tax evasion.